Words:

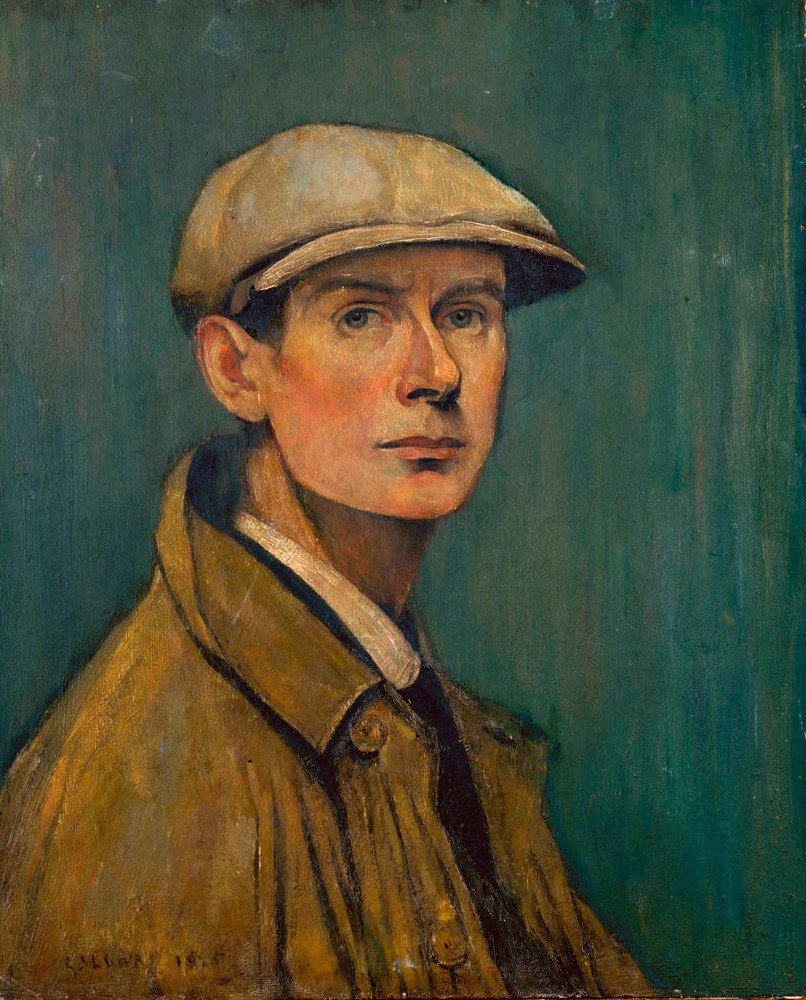

Laurence Stephan Lowry gave artistic life to the industrial north of England. Although famous for the match-stick men style protagonists of his artworks, it was the mundanity and ritualism of working-class life that has made his work integral to the way we remember that era of British history.

Share:

-

The places that Lowry painted don't exist anymore and neither do the people. One of his most famous pieces, Going to the Match (1928), depicts swathes of nameless and faceless people - the proletariat - heading towards a football ground. The scene uses washed-out colours - it's grey and gloomy, a familiar scene to people from the industrial north.

These people inhabit a joyless scene, walking towards a game of football out of duty - it's a ritualistic part of their lives. One can imagine that they've just finished their night-shift and headed to the match via the pub. They're dogged, dirty, work-worn and essential.

The Lowry figures are the people that maintain the cogs of British industrial society. They work in factories and mines - their career is an occupation of duty. They are agents with no agency consigned to the gloom and doom of fate as defined by the era they were born.

Although the football ground is oft associated with ecstasy and joy, this is part of the same extended backdrops that dominates the majority of his work. There is very little to differentiate this from the workhouses in his other paintings. In 1930, Coming From The Mill saw the light of day - it was more of the same, but different. The heavy heads and the well-worn shoes of factory workers knocking-off - heading back to their families, the pub. They were returning from one life to another.

Smog dominates the sky, ominously casting a grey tint over everything and everyone below. There's no window for God to reach his hand down - there are no miracles in places like this. It's all a ritual - putting one foot before the other. Repeat, repeat, repeat. The figures are stuck in a loop, there's no way out. The frame contains their life in microcosm.

Anyone who has visited the areas depicted in his paintings will see the vestiges of the lives that were lived back then. Now these factories exist mainly dormant, skeletal red-brick and corrugated steel buildings that pepper the skyline are a darker reminder of the past - yet somehow a past that is solemnly missed. No one could say life was easy back then, but at least people had each other, at least there was order and in some greater sense - meaning.

There was a time that the working-class identity revolved around the willingness to work in jobs that powered the economy. These days were defined by a pride that has long since been snatched by the cruel neoliberal economic policies of Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government.

Privatisation drove a steak through the heart of factories and mines - means of production. Lowry captured the dreariness and desperation, even hopelessness of these scenarios. At the time it might have been unimagineable that life could have gotten much worse, but now looking back with rose-tinted glasses reflecting our mobile-phone lights, maybe it has. People's jobs now have titles that seem oxymoronic, unable to actually articulate what it is they do. It's not difficult to image a contemporary Lowry with men and women in suits, eating their lunchtime meal deals outside huge glass skyscraper - equally as lost, equally as part of a machine. Only this one lacks the solidarity - we're too deep into it to consider that solidarity is our escape.

Back then you were only a worker, but at least you knew what you were doing. You had your job and you'd be proud to do it well. When you brought your wage-slip back home, it was an honest wage. The bread on the table was earned with blood, sweat and tears - something the whole family could be grateful for. Due to intense modernisation and the seismic surge of the tertiary industries, we feel more disconnected from the goods that we consume - probably because we can't even image how they are produced or by whom.

Lowry's paintings didn't need to highlight the faces of th people - their zombie-like marches in the dull environ said more than enough. It's easy to romanticise those days - talk to a grandmother or grandfather and ask them what it was like. They'll tell you it was hard, but they'll tell you that things are harder now - even if they can't articulate why. The look in their eyes might be one of loss, loss of a time, loss of an identity - all of which are captured and documented in Lowry's art. Despite the death of a way of life, his artwork is there to remind us how far we've come and how far we have left to go.

Share:

-

More like this:

-

-

-